Cognitive Hacking and Information Operation: Specter in the Online Marketplace of Ideas

In the age of social media, our way of interacting and sharing information has forever changed. Once information used to travel slowly and undemocratically but is now only contrasted by its ability to spread to all corners of the world at the speed of a click. Although social media has brought significant value to our lives, they have simultaneously facilitated the spread of disinformation, propagated toxicity, and enabled extreme violence against minorities through coordinated efforts by malicious actors.

Don't get me wrong! This is not to suggest that we should deem social media development as a regression in our society. These platforms have enabled us to keep in touch with our loved ones, assisted mass movements before natural disasters, and even facilitated citizens to coordinate actions to overthrow dictatorial regimes. However, like any significant leap in human connectivity, it has a basket of benefits for us to enjoy. It also brings baggage of threats that need to be checked and mitigated.

As more of our lives have moved online, we have also turned to online sources as our primary destination for news. Apart from credible journalistic sources, we have also developed an appetite for information from online blogs, forums, and groups that share beliefs and values identical to our own (a.k.a. echo chambers). Although these new platforms have made it possible to stay connected, it has also released a specter amongst us - Cognitive Hacking.

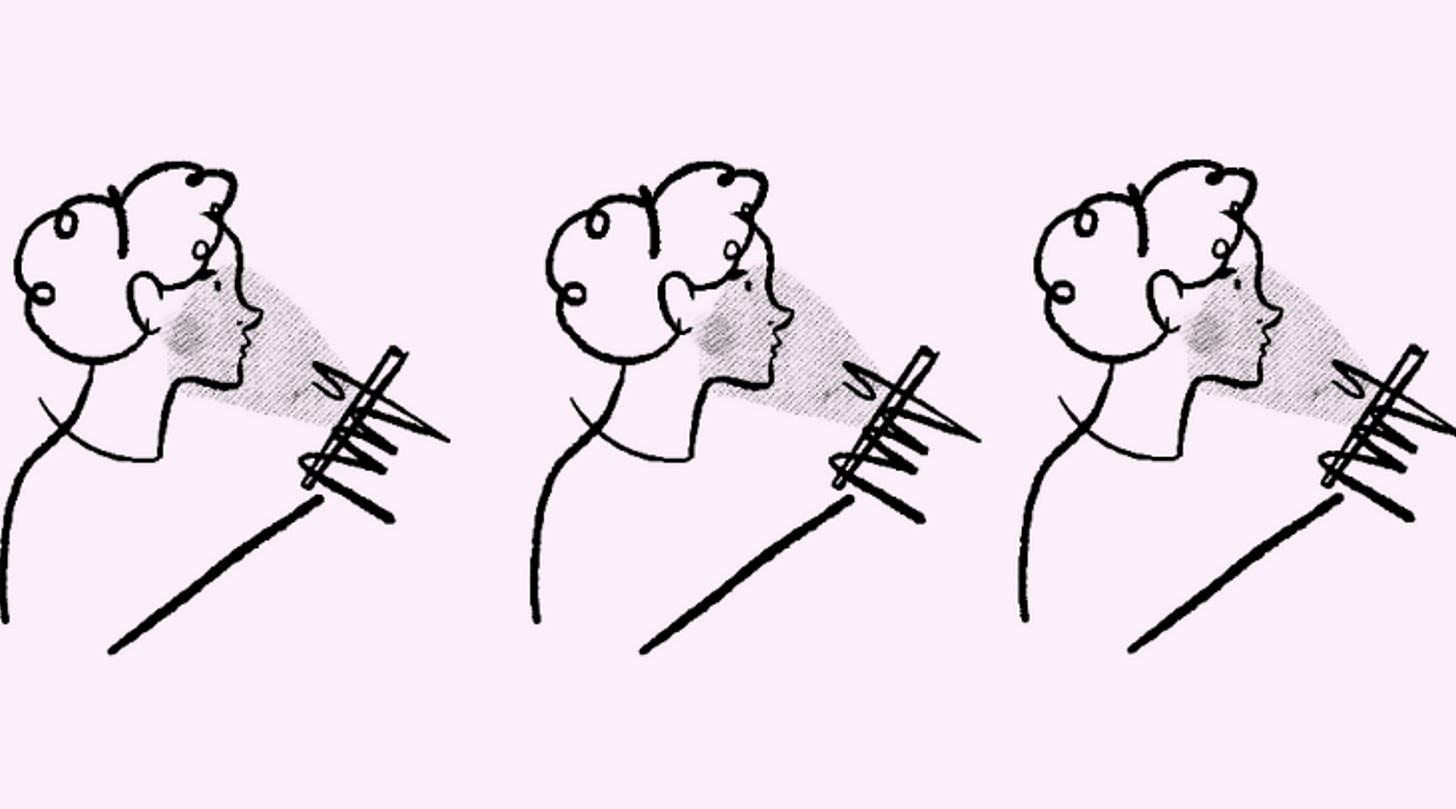

Cognitive hacking can be defined as the attempt at manipulating information in an effort to change users’ perceptions and opinions on a particular topic. These altered sensitivities can cause the users to alter their behaviors in ways that harm a particular group or person.

Cyber-mediated changes in human behavior, social, cultural, and political outcomes have unlocked a new frontier of threats to our society and national security. The threats to national security should be seen as both physical and non-physical in nature. The physical dangers are where state or non-state actors can cause damage by targeting critical assets, infrastructure, or individuals to instill fear, disrupt economic activities, or disrupt the political ecosystem of a country. All in all, the damage caused by these activities is physical, tangible, and/or quantifiable. The non-physical threats include propaganda, disinformation campaigns, etc. that seek to create disagreement, fear, and discontent amongst a population in an effort for the target to implode by internal conflict. In recent years we have witnessed significant development in this non-physical form of attacks. The ability to attack an adversary without physical means has given rise to a state of conflict known as "hybrid warfare" facilitated through "asymmetric capabilities. " Here, information-based attacks sometimes are not just complementary to traditional warfare tactics but have become an end in itself.

It is also essential to clarify the term "fake news" here. In recent years Donald Trump made the expression famous, although it had long existed before he started to use it. This term is commonly used in a casual conversation to refer to a factually incorrect piece of information. However, in academic writing, you will hear "disinformation" and "misinformation" instead. These terms may seem synonymous too, but they differ when used in the discipline. Mis and Dis-information can both be seen as "wrong or misleading information"; however, Misinformation is sharing false information believing it is correct, while Disinformation is the deliberate spread of incorrect information to cause harm.

These attacks seek to target the societal bonds that exist within our communities. Technological developments have facilitated more excellent connectivity of individuals through social media platforms and have created the ability to manufacture and spread propaganda at a grand scale. By weakening trust in national institutions, consensus on national values, and commitment to those values across the international community, an actor can win the next war before it has even begun.[3]

This emerging information warfare leverages advances in micro marketing, psychology, persuasion, and understanding of the social sciences to effectively implement coordinated information operations. Recently, we are experiencing the threat present in the forms of coordinated cyber-bullying, extremist group recruitment, and increasing civil unrest by propagating polarizing opinions.

This goal of cognitive hacking is achieved through state and non-state actors taking part in ‘Information Operation’ and ‘Influence Operations’. Although the terms are often used interchangeably by some analysts, for our purpose, these two terms will be referred to distinctly in our work. Information Operations can be any effort to introduce a new information element or propagate existing information fragments in the network. An example of this could be a threat actor reproducing a particular piece of Covid-19 disinformation to confuse readers about the necessary Covid-19 precautions. On the other hand, Influence Operations is a coordinated attack on a significant population to illicit a particular response from them that helps the adversary get closer to its goal. An example of this could be the spread of specific disinformation that enrages the population and convinces them to vote for one candidate over another.

Understanding the Maneuvers of Information Operation ( copied from "An Emerging National Security Requirement" by David M.Beskow and Kathleen M. Carley):

The maneuvers of any information operation on a social network can be categorized into two subcategories, Narrative Maneuver and Network Maneuver. Though this classification is part of the Social Cybersecurity methodology, which we will explore in the following article, it is helpful to look at information operations through this categorization to understand the threat better. I think Carley and Beskow do a great job explaining so I will try to keep as much of the original language as possible.

1) Narrative Maneuver: Manipulation of information and the flow of information in cyberspace. Examples of information maneuvers include:

a) Misdirection: Introducing unrelated divisive topics into a thread to shift the conversation.

b) Hashtag latching: Tying content and narratives to unrelated trending topics and hashtags.

c) Smoke Screening: Spreading content (both semantically and geographically) that masks other operations.

d) Thread jacking: Aggressively disrupting or co-opting a productive online conversation.

2) Network maneuver: Manipulation of the social network. In these maneuvers, an adversary is focused on changing online group structures, impacting who is connecting to whom, and who is no longer connecting to whom. These maneuvers impact the average degree, density, and modularity of the network:

a) Opinion leader co-opting: Receiving acknowledgment from an opinion leader and leveraging their authority to spread a particular narrative online.

b) Community building: Building a community around a topic, idea, or hobby and injecting a narrative into this group.

c) Community bridging: Injecting ideas of group A into group B. Requires the actors to infiltrate group B, followed by slowly adding retweets or shared ideas from group A into B.

d) False generalized other: Promoting the false notion that a given idea represents the consensus of the masses and, therefore, should be an accepted idea or belief by all.

Recent Examples:

1. V_V movement (research by Graphika):

On Dec. 1, Meta removed a threat network of authentic, duplicate, and fake accounts. This network originated in France and Italy and was mobilized to spread disinformation regarding the Covid-19 vaccine. Additionally, the network of users harassed those advocating for the vaccine. This operation identified preexisting anti-vaccine narratives and then propagated the messages that seemed to have the most significant engagement. The movement created its own description of identity around its activities. It projected itself as a “collective of internet warriors” participating in a guerilla “psychological warfare” campaign against the oppressive forces of “medical Nazism."

2. Transphobic misinformation trends on Twitter after Highland Park shooting (report by DFR Lab at Atlantic Council):

Following the Highland Park shooting, tweets created a narrative to promote transphobic sentiments online as some actors reported that the offender was a transgender person. This was a classic case of a disinformation campaign since it was known that the gunman wore women's clothing to hide his facial tattoos and did not provide any evidence of being a transgender individual in his past. This strategy was similarly used following the shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde when 4chan facilitated the spread of an innocent transgender person's picture as the shooter.

3. Twitter Network Used Copyright Complaints to Harass Tanzanian Activists (research by Stanford Internet Observatory):

In December 2021, Twitter announced that it had recently suspended 268 accounts. These accounts tend to be supportive of the Tanzanian government. These accounts weaponized copyright reporting to target accounts of Tanzanian activists. According to Twitter, many of the African personas used in this campaign were previously Russian personas. This provided some indication that the suggesting the operation may have been partially outsourced to a Russian-speaking country.

4. Pro-Russian Facebook assets in Mali coordinated support for Wagner Group, anti-democracy protests(report by DFR Lab at Atlantic Council):

A network of Facebook pages was discovered that seemed to be promoting pro-Russian and anti-French narratives. This maneuver simultaneously pulsated support for Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary group, days before the paramilitary organization was to arrive in Mali. The information on these pages also promoted a narrative that called for postponing the democratic elections in the country.